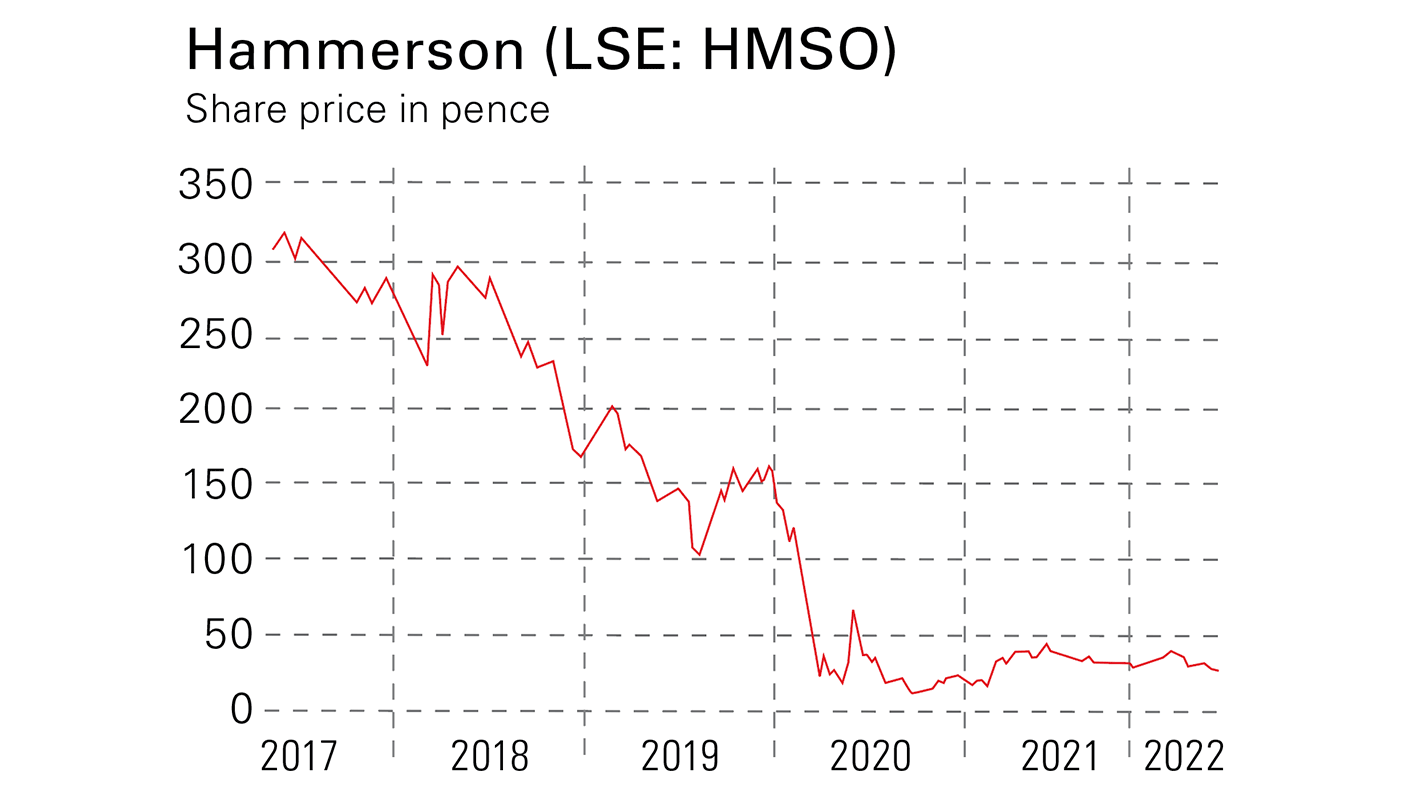

Everyone’s heard of London’s “swinging 60s” cultural centre Carnaby Street. It’s now part of the property portfolio of Shaftesbury (LSE: SHB), a Reit that invests exclusively in the heart of the capital’s West End. Shaftesbury owns a total of 1.9 million square feet, plus another 0.3 million square feet in joint ventures, across Chinatown, Covent Garden, Fitzrovia and Soho. The portfolio split as at end-September 2021 was 37% hospitality and leisure, 27% retail, 18% office and 18% residential. Net property income for the financial year to 30 September 2021 was £65m, down from £73m and £98m in the two prior years, due to the fallout from Covid-19 hitting the company’s tenant base. After allowing for downward property revaluations of £197m, Shaftesbury made an operating loss of £157m. That led to the axing of the dividend.However, net debt at the financial year-end had fallen to £748.5m, down from £987m 12 months before. What’s more, Shaftesbury has just disclosed that the indicative valuation of its wholly-owned portfolio as at 31 March 2022 was £3.26bn. That’s up around 7.5% from 1 October 2021, which in turn follows a 5.2% like-for-like increase in the six months to 30 September 2021.This all indicates that Shaftesbury’s NAV is quite a bit higher than its end-September 2021 level of £2.37bn. Despite that, the current market cap is just £2.3bn – ie, no more than its NAV at the end of the last financial year. In other words, this REIT is clearly cheap. And unlike Carnaby Street the shares are right out of fashion, having dropped by 40% over the last four years. For long-term investors, they look well worth tucking away.Shaftesbury is an owner of prime London property, and even though its shares are well down on where they used to be, it’s certainly not shunned. For a real deep-value play with the scope to reward long-term investors, but greater risks, look at assets that nobody loves. Hammerson (LSE: HMSO) is a very interesting case. It’s a commercial property behemoth that owns city centre assets in major cities in Britain, France and Ireland, as well as several UK retail parks. The company’s key UK sites include London’s Brent Cross, Birmingham’s Bullring & Grand Central, Bristol’s Cabot Circus, Croydon’s Centrale & Whitgift, Leicester’s Highcross, Southampton’s Westquay, Reading’s Oracle and Aberdeen’s Union Square. In short, it’s a long list of the kind of shopping centres that are supposed to be hugely challenged by the shift to online retail.After downward revaluations of its properties, Hammerson made a £429m loss in 2021. Yet asset disposals lowered net debt by more than £400m to £1,819m. Further, shareholders’ funds as at 31 December 2021 were £2,746m, equivalent to 64p per share. Compared with the share price of 29p – down by more than 90% over the last 15 years – this equates to a discount to NAV of around 55%. That looks seriously cheap!It’s true that this NAV could well fall further in the event of deteriorating economic and interest rate developments. Nonetheless, Hammerson’s current valuation seems to be discounting a near-Armageddon scenario in commercial property values. Anything less than this is likely to boost the stock price over time. For long-term value seekers, this is surely a share to lock away.

Everyone’s heard of London’s “swinging 60s” cultural centre Carnaby Street. It’s now part of the property portfolio of Shaftesbury (LSE: SHB), a Reit that invests exclusively in the heart of the capital’s West End. Shaftesbury owns a total of 1.9 million square feet, plus another 0.3 million square feet in joint ventures, across Chinatown, Covent Garden, Fitzrovia and Soho. The portfolio split as at end-September 2021 was 37% hospitality and leisure, 27% retail, 18% office and 18% residential. Net property income for the financial year to 30 September 2021 was £65m, down from £73m and £98m in the two prior years, due to the fallout from Covid-19 hitting the company’s tenant base. After allowing for downward property revaluations of £197m, Shaftesbury made an operating loss of £157m. That led to the axing of the dividend.However, net debt at the financial year-end had fallen to £748.5m, down from £987m 12 months before. What’s more, Shaftesbury has just disclosed that the indicative valuation of its wholly-owned portfolio as at 31 March 2022 was £3.26bn. That’s up around 7.5% from 1 October 2021, which in turn follows a 5.2% like-for-like increase in the six months to 30 September 2021.This all indicates that Shaftesbury’s NAV is quite a bit higher than its end-September 2021 level of £2.37bn. Despite that, the current market cap is just £2.3bn – ie, no more than its NAV at the end of the last financial year. In other words, this REIT is clearly cheap. And unlike Carnaby Street the shares are right out of fashion, having dropped by 40% over the last four years. For long-term investors, they look well worth tucking away.Shaftesbury is an owner of prime London property, and even though its shares are well down on where they used to be, it’s certainly not shunned. For a real deep-value play with the scope to reward long-term investors, but greater risks, look at assets that nobody loves. Hammerson (LSE: HMSO) is a very interesting case. It’s a commercial property behemoth that owns city centre assets in major cities in Britain, France and Ireland, as well as several UK retail parks. The company’s key UK sites include London’s Brent Cross, Birmingham’s Bullring & Grand Central, Bristol’s Cabot Circus, Croydon’s Centrale & Whitgift, Leicester’s Highcross, Southampton’s Westquay, Reading’s Oracle and Aberdeen’s Union Square. In short, it’s a long list of the kind of shopping centres that are supposed to be hugely challenged by the shift to online retail.After downward revaluations of its properties, Hammerson made a £429m loss in 2021. Yet asset disposals lowered net debt by more than £400m to £1,819m. Further, shareholders’ funds as at 31 December 2021 were £2,746m, equivalent to 64p per share. Compared with the share price of 29p – down by more than 90% over the last 15 years – this equates to a discount to NAV of around 55%. That looks seriously cheap!It’s true that this NAV could well fall further in the event of deteriorating economic and interest rate developments. Nonetheless, Hammerson’s current valuation seems to be discounting a near-Armageddon scenario in commercial property values. Anything less than this is likely to boost the stock price over time. For long-term value seekers, this is surely a share to lock away.